White Labs and Green Malt

Malted grains are the one of the main sources of fermentable sugars in the brewing and distilling industries, and it also contributes significantly to the color, flavor and aroma of the final products. However, malt production is a water and energy intensive process, conventionally separated into three key steps: steeping, germination and drying/kilning. Accounting for >70% of the total energy requirements, reducing or eliminating the kilning process would greatly contribute to reducing the carbon footprint.

Craft breweries and grain-based distilleries generally consume more raw material per product than large producers, mainly to improve flavor but also due to smaller and less efficient production units. This potentially contributes to higher carbon footprints in craft products than larger producers. However, some of these impacts can be reduced and mitigated by locally sourcing ingredients and improving the water and energy utilization in the processes.

Green Malt, or freshly germinated grains but not yet dried or kilned, has been proposed as an alternative to save water and energy in the brewing and distilling process. These grains present higher α- and β-amylase activity than normal base malt, with a great capacity to convert starch into fermentable sugars and contribute to higher levels of nutrients for the fermentation. Introducing Green Malt in the process could provide an opportunity for craft producers to gain more control of their supply chain by partnering directly with local farmers to reduce their carbon footprints and create product innovations. However, some technical and flavor challenges limit the wide application of Green Malt in the craft brewing and distilling industries.

Almost all of White Labs yeast and bacteria propagation is based on malt products, being malted grains or liquid malt extract, and that carries a large CO2 footprint. As far back as 2009, the White Labs team started looking at Green Malt as a raw material to lower our energy and water inputs. We went as far as growing our own barley, a full 20 tonnes, in a field in Davis, CA. We couldn’t overcome some of the technical challenges and implement that idea back then, but we didn’t give up because we believed that it could help us improve our process.

Sustainability needs to be a long term priority, and some efforts to make a process more environmentally friendly might take a very long time. After many years and trials, we found the right partners and equipment to turn this idea into reality.

Empirical, a Copenhagen-based company that produces grain-based spirits, shared the same concerns and goals as White Labs, so our Copenhagen team worked together with them to assess the implementation of Green Malt in a craft brewery/distillery production.

Germination Trials

Figure 1. Basic setup for steeping and germination of malt.

Figure 1. Basic setup for steeping and germination of malt.

Making our own malt gives us the freedom to source barley varieties with a wide range of color and flavor profiles, that are not usually available from large maltsters"

-Troels Prahl, Director of Innovation

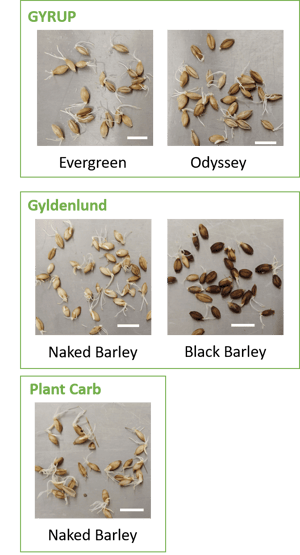

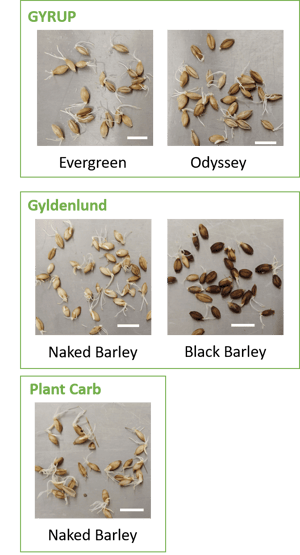

For a complete overview of the process, we reached out to the University of Copenhagen for a thorough microbiological profile and to Glycospot to assess the development of the different brewing-relevant enzymes. White Labs and Empirical started sourcing various barley varieties from local organically-certified farmers (GYRUP, Gyldenlund, and Plant Carb) and tested their germination properties, enzyme content, and flavor profile.

To test multiple conditions and grain varieties simultaneously, we developed a bench-scale setup based on simple equipment available in most craft breweries and distilleries (Fig. 1). This system allowed for easy filling and draining from the bottom. An air source placed under the false bottom allows for aeration of the grain both during steeping with water and germination. High moisture air was produced by bubbling compressed air through water immediately before entering the germination vessel.

Applying the bench-scale setup, we could evaluate the minimum conditions (temperature, time, volumes) to efficiently promote germination and evaluate if we could fit malting into a production schedule. Our steeping and germination schedule was designed to minimize the duration of all steps while still fitting a normal working day (Table 1). Temperature control was important, as malting is a fine balance between achieving enough enzyme activity and leaving plenty of starch for brewing.

|

| Step |

Duration |

| Steeping |

1st steeping |

6 hours |

| Air rest |

18 hours |

| 2nd steeping |

6 hours |

| Germination |

Up to 48 hours |

Table 1. Steeping and germination schedule. Activities were performed in a temperature-controlled room at 16 °C.

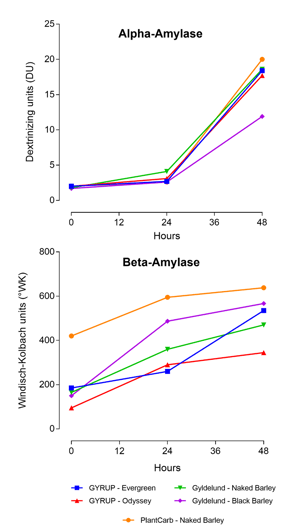

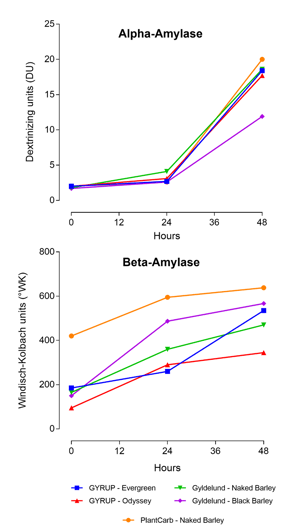

Our system could efficiently bring the moisture content of the different grains above 44% and keep it at that level, inducing all the grains to start germinating. We measured the alpha- and beta-amylase activity of the different varieties during the steeping and germination process to evaluate the minimum amount of time required to achieve efficient conversion (Fig. 2). Including the steeping steps, we could efficiently germinate all barley varieties within 72 to 96 hours (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Enzyme activity of the different barley varieties during the 48 hours of germination. An increase of alpha-amylase (Dextrinizing units) was observed in all trials. Naked barley varieties showed the highest beta-amylase activity (Windisch-Kolbach units). White bar = 1 cm. Germination was observed across all different barley varieties at 48 hours.

To assess how the natural microbiota of the grains and water would influence the malting process, we partnered with the Food Department at Copenhagen University and used their facilities and expertise. Following their recommendation, the germinating grains were sampled for microbial counts at the following steps during germination: grains, after 2nd steeping, 2nd steeping water, after 24h of germination, and after 48h of germination.

Facultative anaerobic bacteria were detected in the range of 5.0-6.2 log10 CFU/mL; yeasts ranged from 2.6-4.3 log10 CFU/mL and molds ranged from 2.5-4.4 log10 CFU/mL. Interestingly, no yeasts were detected on the two varieties from Gyldenlund, and no mold was detected on the Black variety from (Gyldenlund).

Isolated colonies from all samples were used for genetic identification. The identified bacteria were mainly known plant-associated bacteria, namely Erwinia spp. and Pseudomonas spp., as well as plant pathogens, including Pantoea spp. and Curtobacterium spp. Interestingly, no lactic acid bacteria species were identified among the 30+ identified colonies across all varieties.

However, this might also be due to the number of isolates picked and incubation conditions. The microbial work also shows that while molds were present in most samples and could be detected in the selective media plates, our process conditions could control mold development in the grains during steeping and germination.

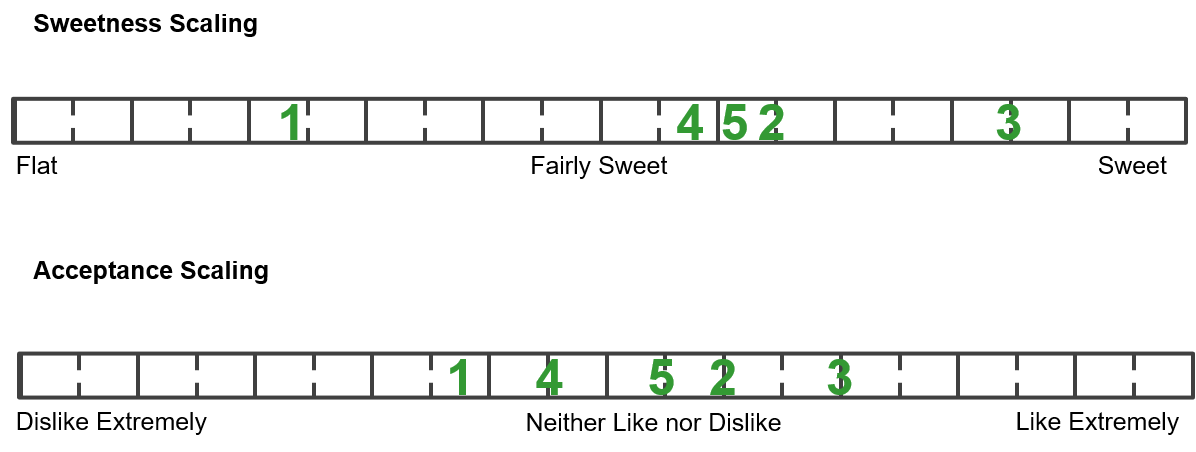

Making your own Green Malt allows you to source locally available barley varieties that work efficiently in your germination system. Still, one of the main opportunities is selecting a barley variety that contributes significantly to your final product's flavor and aroma profile. All tested barley varieties presented similar germination efficiencies and comparable diastatic power, so with the support of the expert taste panel from Empirical, we moved to taste trials.

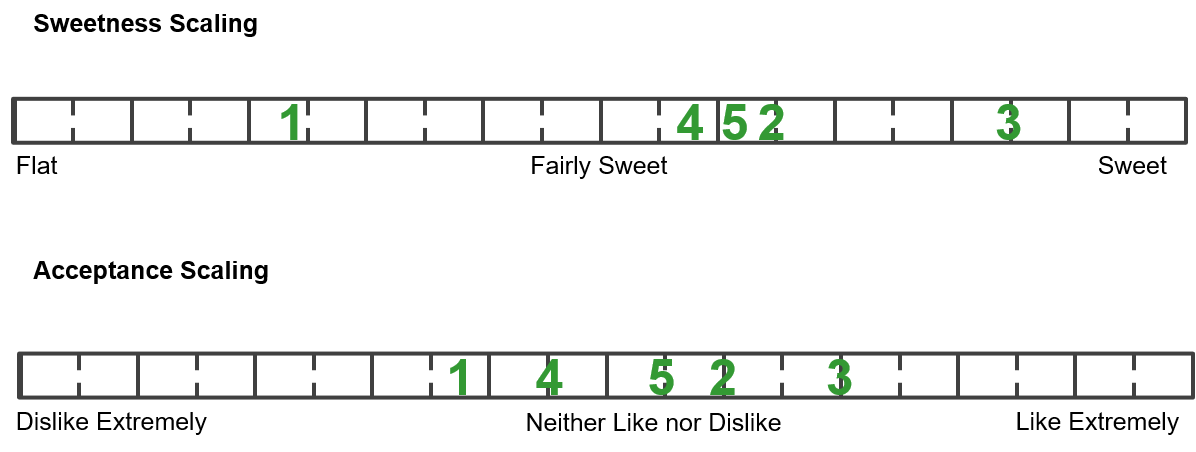

Wort was prepared from each of the Green Malt samples, and the gravity and pH were measured (Table 2). The wort samples were cooled to a similar temperature and blind tested by the tasting panel. One of the varieties stood out, Odyssey, both in the amount of released sugar and the overall flavor contribution (Table 2).

Table 2. Green Malt blind tasting test. Identification, brewing parameters and average results for sweetness and acceptance for each sample.

|

| Sample No. |

Sample Name |

Gravity (°P) |

pH |

Tasting Temp (°C) |

| 1 |

Gyldenlund - Black Barley |

9.5 |

5.2 |

19.5 |

| 2 |

PlantCarb - Naked Barley |

10.7 |

5.3 |

20.3 |

| 3 |

GYRUP - Odyssey |

12.1 |

5.3 |

19.6 |

| 4 |

GYRUP - Evergreen |

11.6 |

5.3 |

20.4 |

| 5 |

Gyldenlund - Naked Barley |

10.6 |

5.3 |

21 |

Pilot Scale Steeping and Germination

Having selected a barley variety with improved flavor and aroma contributions that were compatible with our simplified germination system, the next step was to scale up and do a pilot-scale run. To scale up our germination system while using as little space in the brewery as possible, we used 200 L drums containing a false bottom to allow filling and draining from the bottom and for aeration of the grain bed. (Fig. 3, left). Moist air flow through the bed was introduced by a pressurized keg of soft water attached by hoses to the bottom of each drum (Fig. 3, right.)

Figure 3. 200L Drums

The first scale-up trial utilized 400 kg of barley, which was weighed and divided into four separate drums, 100 kg each. The grains were washed with soft water before being immersed in water for the first steeping, drained, and allowed to air rest overnight, followed by a second steeping and germination period (Table 3).

Table 3. Steeping/germination protocol for scale-up trial.

| Process |

Description |

| 1ST STEEPING |

∙ 4-6 hours at 16-18°C in drums

∙ Mixed and temperature recorded

∙ Air compressor was attached to bottom valve and roused once to keep oxygen levels high

∙ Drained

|

| AIR REST |

∙ 12-18 hours at 16-18°C in drums

∙ Mixed and temperature recorded

∙ Air compressor was attached to bottom valve

∙ High moisture air forced through the grain bed overnight

|

| 2ND STEEPING |

∙ 4-6 hours at 16-18°C in drums

∙ Mixed and temperature recorded

∙ Air compressor was attached to bottom valve and roused once

∙ Drained |

| GERMINATION |

∙ 24 hours at 18-20°C in drums

∙ Mixed and temperature recorded

∙ Air compressor was attached to bottom valve

∙ High moisture air forced through the grain bed overnight |

Special attention was given to mixing the grain bed to avoid overheating due to the exothermic activity of the respiring grains and prevent the rootlets from tangling together. This further helped dispel any built-up CO2 and keep the grains oxygenated. Temperature was controlled and monitored throughout using a long thermometer capable of reaching deep into the grain bed.

The entire “malting” period of Green Malt took approximately 48 hours. Germination was deemed finished when the rootlets had grown considerably outside the grain, confirming that the endosperm was well modified. The production of brewing-relevant enzymes (ɑ-amylase and β-amylase) during the steeping and germination steps was determined (Table 4).

The production of ɑ-amylase increased significantly over the germination process and reached values higher than the lab-scale tests at 24 hours (Table 4). Once the grains were deemed sufficiently germinated, around 24 hours, they were transferred to a mash tun and subjected to continuous steep milling (or wet milling) (Fig.4).

Table 4. Enzyme activity over the germination step of α-amylase and β-amylase.

|

| Step |

Time (Hours) |

α-amylase

(Dextrinizing units) |

β-amylase

(Windisch-Kolbach units) |

| Germination |

0 |

5.14 |

256.43 |

| Germination |

18 |

9.85 |

245.46 |

| Germination |

19 |

11.37 |

- |

| Germination |

20 |

12.9 |

216.31

|

Brewing, Fermentation, and Distilling

Figure 4. Green Malt & Mash Tun

Figure 4. Green Malt & Mash Tun

To test the suitability of Green Malt for brewing applications and assess its flavor and aroma contribution to a distilled product, the Empirical team designed a brewing and fermentation schedule that would maximize the contribution of the freshly malted grain. The 400 kg of grains and 1000L of water were mixed, ground through a wet hammer mill, and sent back into the mash tun in one continuous stream.

After mashing (Fig. 5, left), the wort was sent through a mesh filter press to remove the grain solids, then a chiller to cool it down and transferred to a fermentation vessel, ready to be pitched with

White Labs Belgian Saison II Ale Yeast (WLP566).

Fermentation commenced at room temperature. Fermentation was monitored daily, noting temperature, pH, and °Plato (Fig. 5, right). After 12 days, the fermented wash of 1000L was transferred to a vacuum still and distilled at 70 mbar between 24°C and 40°C for 24 hours. Low wine was collected and distilled again 70 mbar between 24°C and 42°C for approximately 24 hours, yielding a spirit. The collected tails from this spirit run were further distilled under the same conditions, yielding more than 100L of spirit (>50% ABV).

The trial process efficiency showed great potential for Green Malt utilization, with a margin for significant time savings on the mashing and fermentation steps in follow-up trials.

Figure 5. Brewing schedule (left) and fermentation curve of the Green Malt wort (right).

Sensory Analysis

The produced Green Malt spirit was evaluated using the Empirical panelist's team of experts in spirits sensory analysis. A descriptive test was carried out whereby the panelists were asked to blindly taste the three prototype products and list the associated sensory attributes. A preference test was also carried out, which involved blind-tasting prototype one (Green Spirit) and another clear spirit at the same ABV. This other spirit, made in-house by Empirical, was made using “traditionally” malted pilsner malt and purple wheat. The panelists were asked to state which of the two spirits they preferred.

Green Spirit received predominantly positive feedback, with the majority of descriptors being favorable: sweet, green, peppery, mineral, fruity, clove, earthy, floral, and nutty. The unfavorable flavor characteristics mentioned were nail varnish or band-aid. In the preference tests, the Green malt spirit was preferred by 71% of panelists compared to the alternative malt grain-derived spirit.

Based on the sensory analysis conducted, Green Malt showed a strong potential for use in the brewing/distilling industry from a flavor perspective. The spirit produced promising results, yielding many top notes like sweet, green, peppery, and floral. The flavor profile was so interesting that new batches of Green Malt spirit were produced, and small-scale trials for producing Green Malt-based beer are underway.

This demonstrates that the Green Malt is capable of producing a clean, tasty spirit, which in itself is extremely versatile. Some potential uses include usage in a canned cocktail, mixed drink, or to be cask-aged

-Lars William, Empirical Co-Founder

Green Malt also shows great potential for application in the production of microorganisms, as it yielded a light-colored wort with high vitamins and micronutrient content, and gravity above 15 °P, allowing for easy dilution to meet strain-specific requirements.

Perspectives on the Potential of Green Malt

Our trials showed that it is possible to germinate several hundred kilograms of barley in a craft brewery/distillery setup with very little extra equipment and footprint requirements. The customized drums can easily be used in other functions and processes to return the investment quickly. Conventional malting processes require a long germination period, as a significant loss of enzyme activity occurs during drying and kilning. The high enzyme activity measured in freshly germinated grains allowed for high conversion in the mash tun even at relatively short germination times (<24 hours). Furthermore, a short germination process minimized rootlet formation, reducing the associated off-flavors detected in the wort and final products. This high enzyme activity opens the possibility of using alternative non-malted grains, like sorghum and buckwheat.

Nevertheless, Green Malt yields grains with a moisture content of 35-45%, and handling those wet grains in the brewhouse poses the main challenge to the successful integration of Green Malt in a brewing operation. The Empirical brewhouse already includes adequate equipment to handle high-moisture grains of different origins, so Green Malt was quickly processed through existing operating procedures. However, a significant portion of the small and mid-size craft breweries and distilleries are not equipped to mill wet grains and mesh filter the porridge-like mash, and some investment could be required. The Green Malt was not tested in a lauter tun, but using Green Malt to replace part of the grist might allow for application in a more conventional system.

The application of Green Malt in a mid-size brewery/distillery showed much potential in the savings of water and energy while allowing for a fast enough process that could be easily integrated into daily operations. The permanent integration of the germination process in the brewery operations could further increase water savings by allowing the reusing of steeping water in multiple germination steps. The in-house process of grains allowed a careful selection of locally available varieties that matched the desired flavor and aroma profile while enabling a closer relationship with local farmers and decreasing transportation-associated carbon emissions.

Conclusion

The Green Malt trials at White Labs started more than 10 years ago, and we learned many valuable lessons during the initial trials, but it took the concerted efforts of different partners to source the grains, implement a new process, and develop a brand new product that highlights the uniqueness of the process.

In any industry, looking at current processes or methods and challenging them is the first step to make advances. Process improvements might range from increased efficiency (time and energy savings) and lower process footprint (water and CO2) to complete re-thinking of the supply chain, as in this Green Malt project. However, testing and implementing innovations, especially when involving sustainability, is a long process that requires the right partners and resources.

Figure 4. Green Malt & Mash Tun

Figure 4. Green Malt & Mash Tun