Making a Kettle Sour with Lactobacillus Cultures

Kettle souring can be a convenient method for creating a crisp, clean, tart beer. Sour beers add variety to the beer menu and can attract new clientele. There are multiple ways to achieve a sour beer. One of the easiest is by using a Lactobacillus culture pre-fermentation in the kettle, allowing you to acidify wort at a higher temperature for quick acid production. Learn more about some tips and tricks on different quick souring.

What is Kettle Souring?

Kettle souring is the process of acidifying the wort before fermentation occurs. Typically done in the kettle with little to no hops, Lactobacillus cultures are pitched in the wort and kept at higher temperatures(90-110°F) until desired pH levels are reached. The wort is then boiled in the kettle to kill the Lactobacillus and other organisms. Then the typical brewing process is followed with hops being added during the boil, then cooled and fermented with yeast.

Not All Strains are Alike

Our Lactobacillus Offerings

Experiment with Blending Strains

Different Lactobacillus sp. range from the amount of perceived sourness they produce. Depending on how they are treated, some produce more lactic acid than others, whereas lactic acid can have a harsher note of sourness. To combat this, we recommend blending different Lactobacillus strains and other acid-producing strains to create a more complex and rounded acid profile.

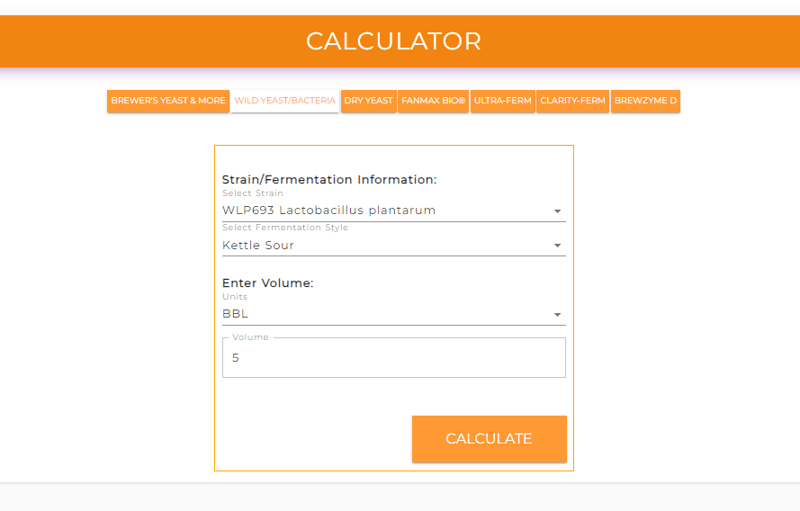

Pitching Rates

Like Brewer’s yeast, the more cells in the fermentation, the faster the souring process will go. For kettle souring, we recommend 1 PurePitch® Next Generation Pro pouch of our Lactobacillus cultures per 5BBLs of wort or 0.35L/1HL of wort. This typically provides a significant pH drop within 24 hours and a maximum drop within 48 hours at the strain's optimal temperatures.

Temperature Matters

Lactobacillus strains can either flourish or flounder at certain temperatures. Here is an example of pH drop from our recommended kettle sour pitch rate. The graph below showcases how quickly the pH dropped at 2 different temperatures.

Figure 1. Lactobacillus "Kettle Sour" acidification at 90°F.

Figure 1. Lactobacillus "Kettle Sour" acidification at 90°F.

Figure 2. Lactobacillus "Kettle Sour" acidification at 110°F.

Figure 2. Lactobacillus "Kettle Sour" acidification at 110°F.

Some considerations for kettle souring include blanketing the wort with CO2 to promote more anaerobic lactobacillus to thrive.

Hop tolerance of lactobacillus strains differ from each other. Too many IBUs halt lactobacillus growth, our recommendation is to use little to no hops for kettle souring (Figures Below).

Figure 3. WLP672 Lactobacillus brevis IBU Growth Tolerance

Figure 3. WLP672 Lactobacillus brevis IBU Growth Tolerance

Figure 4. WLP677 Lactobacillus delbrueckii IBU Growth Tolerance

Figure 4. WLP677 Lactobacillus delbrueckii IBU Growth Tolerance

Troubleshooting Off-flavors

When the wort is fermented with Lactobacillus and >100°F, the potential for food pathogens arises. It’s important that the wort is clean and the pH starts dropping quickly. If some unwanted organisms arise, one of the classic off-flavors, butyric acid, can be present. The smell of baby vomit is almost impossible to get rid of or blend out, so avoiding it in the first place is the best practice. All of these organisms would be killed after the boil, but starting with a pre-acidified wort can help prevent this from occurring.

Co-Ferment with Saccharomyces

One of the considerations for kettle souring is taking up brewhouse tank time. The acidification process takes kettle time and space, which can hold up other beer production timelines. Breweries have been trying different ways to explore this conundrum.

A quick sour can also be during fermentation. We developed a specialty blend of Kveik yeast and Lactobacillus sp. designed to pitch during primary fermentation to create a unique co-ferment of yeast and bacteria.

Utilizing Kveik's uniqueness of a clean aroma profile at higher temperatures, this blend can be used between 90°-100°F (32°-38°C), fermentation and souring can be completed within 72 hours. It's recommended to keep wort hopping low and IBU's below 5-7 to ensure the bacteria is not inhibited, then dry hopping once desired sourness is reached.

The main consideration is further contamination, as dry hopping does not kill the lactobacillus but makes them dormant. This could lead to lactobacillus growth in unwanted places if not controlled or monitored.